Team members: Pitkänen, T., Agullo, M., van Veen, M., Habib, I., Krojgaard, L., Phi, V.

Problem Statement

Faecal contamination of drinking water and subsequent waterborne gastrointestinal infection outbreaks are a major global public health concern (World Health Organization (WHO)). Human and animal faeces may contain pathogenic microbes (bacteria, viruses, protozoans and helminths). Preventing fecal contaminated water from gaining access to treated waters of surface and ground waterworks is essential in order to maintain water quality. It is essential that immediate actions are taken following in cases when fecal contamination of drinking water is suspected or evident. According to Hunter et al. , full emergency level actions need to be initiated in those cases, including a water avoidance or a boil water advisory. When tap water might be contaminated or is known to be contaminated with fecal pathogens, water utilities or public health authorities commonly issue the public to boil water before consumption, according to Mayon-White and Frankenberg . Some water utilities may give a boil water advisory proactive, as the risk for water contamination may increase during repair works. The major part of the boil water advisories is however issued after water quality complaints or when water quality analysis utilizing Escherichia coli indicate the presence of fecal contamination. The boil water advisory is given to reduce the risk of drinking waterborne gastrointestinal illnesses, but the effectiveness of the risk reduction is affected by many factors. These include the fact that after the contamination is detected and boiling water notice issued and received, people have drunk the contaminated water. Some of the persons might not even receive the advice and of those who receive it, not all follow the instructions (precisely). The notice may be taken more seriously and then followed precisely in cases when the water is truly contaminated. On the contrary, in proactive cases, when there is no contamination present (only increased risk of contamination), the notice might not have the same efficacy. The length of the contamination event may also affect the interest of people to boil their water.

Problem formulation: This case study evaluated the effectiveness of boil water advisories in reducing the risk of infection for water consumers.

Hazard Identification

In this chosen city surface water is used as source of drinking water after treatment. We modeled a hypothetical breakdown, for one day, at the water treatment plant. In this scenario, all surface water is, untreated, led directly to all taps. In our case the population of the city is 100,000 people, they all have water from the same treatment plant. Surface water is often fecally contaminated and may contain a wide range of faecal pathogens, such as Campylobacter jejuni, E. coli O157, rotavirus, norovirus, Cryptosporidium and Giardia. In this study, based on the known prevalence in the surface water, being common causes of waterborne outbreaks, the pathogens C. jejuni and Cryptosporidium were selected to be included in this assessment. Boiling the water for 3 minutes is considered effective to kill all pathogens – no infection risk if boil water notice is followed precisely.

Campylobacter

Campylobacter is considered the most important bacterial agent in waterborne diseases in many European countries (Stenström et al. ; Furtado et al. ) - a large number of outbreaks of Campylobacter have been reported in Sweden for example, involving over 6000 individuals (Furtado et al. ). Issues with Campylobacter in drinking waters tend to be a post-treatment problem, due to situations such as broken sewers. Campylobacter spp. have been isolated from rivers (Arvantidou et al. ; Obiri-Danso and Jones ), lakes (Arvantidou et al. ), groundwater (Savill et al. ) as well as drinking water (Alary and Nadeau ; Savill et al. ; Vogt et al. ). The occurrence of the organisms in surface waters has also proved to be strongly dependent on rainfall, water temperature and the presence of waterfowl (WHO ).

Cryptosporidium

Cryptosporidium has been well described as one of the most important pathogens in waterborne outbreaks in many different countries (Proctor et al.1998; MacKenzie et al. 1995). The most important one is the well known outbreak in Milwakee (USA) in 1993, where more than 400,000 people were infected. Cryptosporidium is a protozoan parasite which can infect both animals and humans. The parasite infects the epithelial cells of the digestive and respiratory tract causing diarrhoea. The incubation period is around 7 days (range 1-14 days) and the disease is often self-limiting with a duration of 6-9 days. Longer duration is often found in AIDS patient where the effect of the infection can be lethal (WHO ). All age group can be infected. Infection can happen through consumption of infected water or food, from animals and humans can give the infection to other humans (WHO ; Fayer ). After ingestion of an oocyte four sporozoites are released and infect the epithelial cells. Cryptosporidium only survives outside a host in the oocyst state where it can live month in cold water (Fayer ).

Exposure Assessment

For the modelling, due to the given time, the next assumptions are made:

- Mixing between treated and untreated water is not considered: the model is for a worst case event

- Boiling for the full 3 minutes is effective in killing C. jejuni and Cryptosporidium (Morbitity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) ).

- All isolates have equal chance of causing illness

- All inhabitants are equally exposed

- Concentrations of reference pathogens were sourced from literature

- The only route of exposure is drinking water.

The purpose of the exposure assessment is to determine the amount, or numbers of organisms that correspond to a single exposure (dose) or the total amount or number of organisms that constitute a set of exposures (Haas et al. ). Amongst three main routes of exposure (ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption), only the ingestion route was taken into consideration in this study as faecal-oral transmission is considered the main route of spreading of enteric diseases. The volume of tap water ingested via drinking is much higher than that for bathing, brushing teeth or preparing food.

Volume ingested via drinking

In this study, we used data published Teunis et al. . Based on the data from Netherlands, the human daily consumption of unboiled drinking water is an average 0.27 liter, and the 95%-interval of the consumption is 0.017 – 1.27 liter.

Fraction of population following the boil water notice

In this study, it was assumed that 100 % of the population will know about the boil water advisory after 24 hours from the beginning of the contamination. Furthermore, it was assumed that 80 % of the population will comply with the advisory and 20 % will not. This assumption was based on the data presented by Karagiannis et al. were 81.8% of population responded to comply with the advisory after a faecal contamination detected by the presence of E. coli in tap water in Netherlands. Most respondents still used unboiled water to brush teeth, wash salads and fruits; a result that is supported by the findings from UK reported by O’Donnell et al., where only 38 % of the population followed the given advices precisely. However, as there was no data available of the tap water volumes ingested through these activities, there were excluded from the assessment.

Dose Response

The risk of infection was calculated using @RISK, applying 10,000 iterations in the Monto Carlo simulations. The modelling is done for C. jejuni and Cryptosporidium. The dose-response models used were β-Poisson model for rotavirus and EHEC infections and the exponential model for helminth ova (Haas et al. ). The equations are:

(a) β-Poisson dose-response model

\begin{align*} P_{inf} = 1 - [1+(d/{ID}_{50})(2^{\frac{1}{\alpha}}-1)]^{-a} \end{align*}

where Pinf is the risk of infection of an individual exposed to a single pathogen dose d

ID50 is the median infective dose

α is a pathogen “infectivity constant”

5.1 Campylobacter

In table 1 the model input for campylobacter is given.

Table 1. Model input for campylobacter

5.2 Cryptosporidium

In table 2 the input for cryptosporidium is given.

Table 2. Model input for cryptosporidium

Risk Characterization

The risk of infection was calculated using @RISK and the results are presented as probability of infection (Pinf) per exposure and number of infected people in the studied population.

6.1 Campylobacter

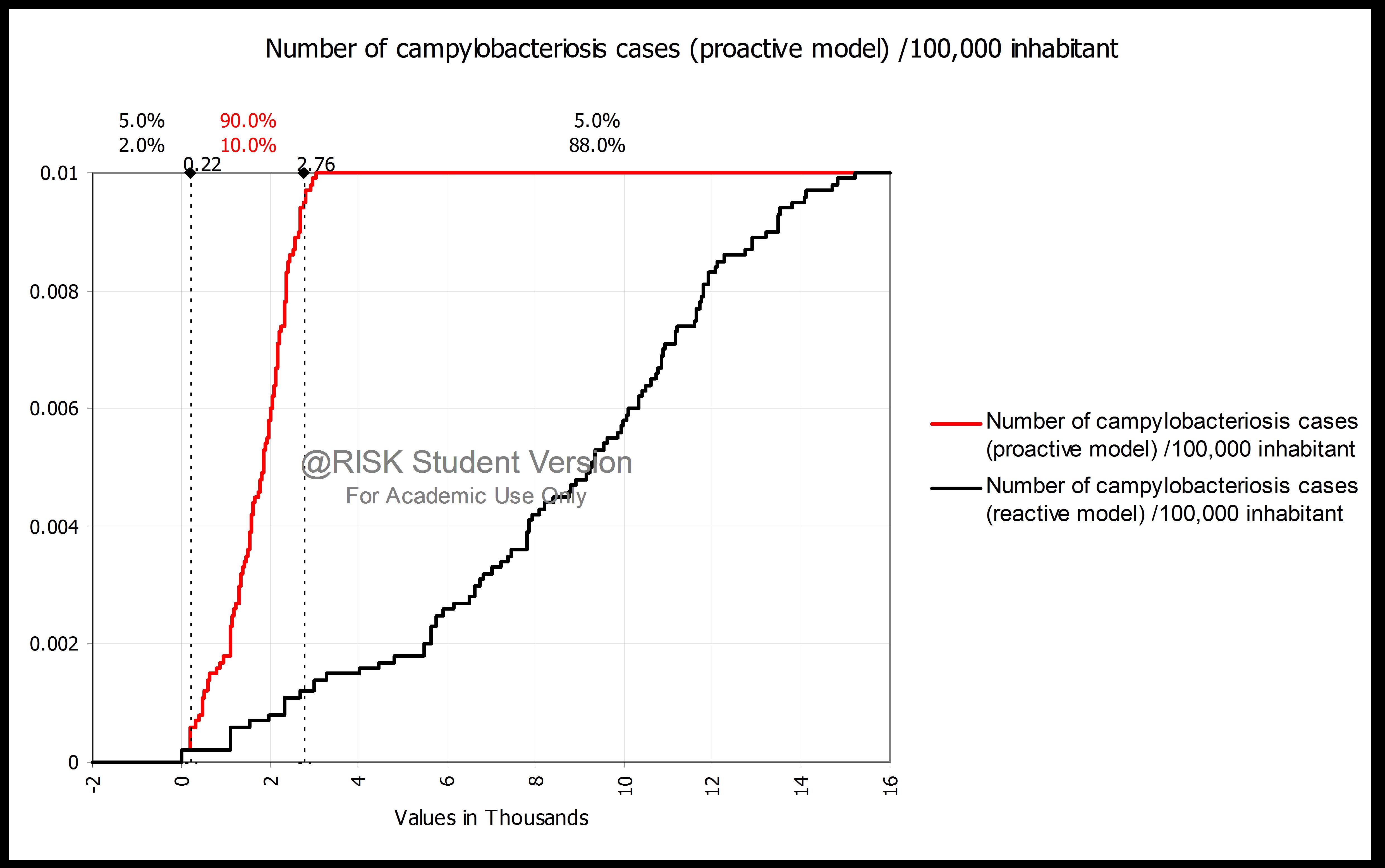

In the graph, figure 1, the results are shown.

Figure 1. Modelling of campylobacteriosis cases

The results are also shown in table 3.

Table 3. Campylobacteriosis case results

| Output | Mean+/-SD | 5% percentile | 95% percentile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of infection with Campylobacter given consumption of contaminated dose | 0.258± 0.116 | 0.0333 | 0.417 |

| Number of cases (proactive scenario) | 1705± 765.89 | 220 | 2756 |

| Number of cases (Reactive scenario) | 8527± 3829 | 1100 | 13779 |

From the table and the graph is shows that probability of infection, given the consumption of contaminated water is 0.258. For the reactive scenario it means that 8,527 people, out of 100,000 people, get infected. In the proactive scenario the number of people is lower, 1,705 people will get infected from drinking the contaminated water.

6.2 Cryptosporidium

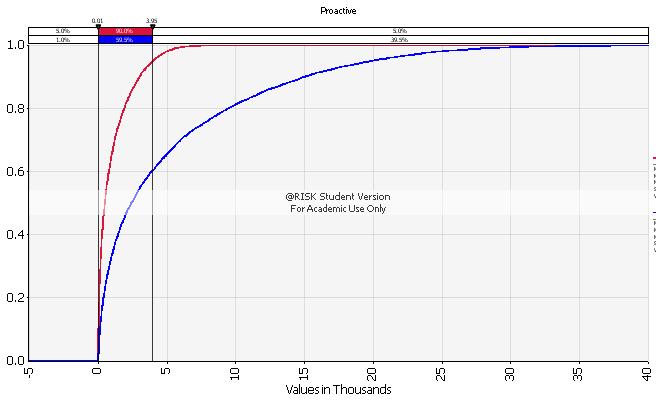

In the graph, figure 2, the results are shown.

Figure 2. Modelling cryptosporidium cases

The results are also shown in table 4.

Table 4. Cryptosporidium case results

| Output | Mean+/-SD | 5% percentile | 95% percentile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probability of infection with Cryptosporidium given consumption of contaminated dose | 0.075 ± 0.093 | 0.0009 | 0.28 |

| Number of cases (proactive scenario) | 1042 ± 1307 | 12.06 | 3873.25 |

| Number of cases (Reactive scenario) | 5212 ± 6534 | 60.29 | 19366.25 |

Risk Management & Communication

It was assumed beforehand that the risk for infection for those persons who will receive the boil water advice in time and also followed the advice, the risk of infection is only theoretical and in practice zero. We have seen important differences between the dose of both microorganisms (Campylobacter and Cryptosporidium) that are due to the fact that we took in to account the infectious oocysts of Cyptosporidium instead the total number.

For risk mitigation, minimizing the presence of the most hazardous microbes in the population would decrease their prevalence in the source waters as well. In cases when the contamination happens despite the prevention efforts, measures increasing the effectiveness of the boil water notice may be applied: e.g. as much as possible information should be provided at the beginning and people need to be informed also about the expected date of lifting the notice. It is important that false alarms (boil water notices without contamination) are prevented as much as possible as they may frustrate people and decrease the efficiency in real contamination cases, but it is important that there is no delays in issuing the notice (no time to wait laboratory results).

Uncertainties

Choice of organisms

In this study only the infection risk caused by Cryptosporidium and Campylobacter was calculated. It is presumably, that following the surface water consumption the prevalence of viral infections would have been numerous as well. Due to the limit of time, viral infections and the effect of multiple infections were left out from this risk assessment. Concentrations of organisms Concentration of certain pathogens differs considerably between different water bodies and seasons. Moreover, the prevalence of certain pathogens is varying greatly between geographical areas and the sensitivity of persons and populations to certain infections differ as well. In this study, quantitative data on Cryptosporidium and Campylobacter numbers in surface waters were used. Break down of system The assumption made that tap water of the whole distribution system was contaminated at equal concentrations will unlikely describe the real situation. A case of total water treatment system breakdown should in the reality be very rare and extreme event. More probable might be that only a small portion of water is contaminated or that the contaminant is diluted with clean water.

Delay

Depending on the characteristics of the contamination case, duration of the consumption of the contaminated water before the boil water notice is issued will vary. It is possible that it will take several days before the water quality problem is discovered e.g. after complaints or when water quality analysis shows the presence of the fecal indicator such as E. coli, instead of one day as it was in our case.

Intake

Daily intake of unboiled tap water (based on data of Teunis et al. ) may underestimate the real consumption, depending on the population structure and climatic conditions.

Boiling advise

In this study, we assumed that heat inactivation at 100 °C for 3 minutes is able to completely kill all pathogenic orgamisms from the water. However, the instructions given regarding the length of boiling differ from 1 minute to 15 minutes. Authorities have recommended water to be microbiologically safe after bringing it to a rolling boil for 1 minute (MMWR ). The WHO technical note for emergency recommends to boil at least 5 minutes and preferably up to 20 minutes (WHO ).

Following advise

Fraction of population exposed is also a variable with great uncertainty. For example, during a large outbreak of cryptosporidiosis in UK, when households were advised to boil tap water before consumption, 88% of the respondents believed that they were following the advice, but still 20% washed food that would be eaten raw in unboiled tap water and 57% used unboiled water to clean their teeth (Willocks et al. ). This means that the simple advice to boil water may be followed only partly due lack of information or due the misunderstandings (Mayon-White and Frankenberg ). Therefore it is important that after boil water notice is delivered by media, it is followed with a detailed instructions letter to the households and further inquiries are handled by giving the basic information through telephone service and via Internet.

For both the microorganism the risk of getting infected is higher than the acceptable level (1/10,000). Looking into the difference between the proactive and the reactive scenario we saw that it is very important to give all the essential information to the residents fast since a 1 day delay will cause around 5 times as many infected people.

In further analysis, the variability of contamination events (surface water/sewage, level and duration of contamination) need to be taken into consideration. Also the uneven distribution of contaminants in the water network need to be taken into acoount. Moreover, DALY’s instead of probability of infection should be used and more attention is needed for risk perception and risk communication.

References

-

Organization, W. H. (2004). Guidelines for drinking-water quality.

-

Hunter, P. ., Andersson, Y. ., Von Bonsdorff, C. ., Chalmers, R. ., Cifuentes, E. ., … Deere, D. . (2003). Surveillance and investigation of contamination incidents and waterborne outbreaks. In Assessing microbial safety of drinking water (p. 205). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=LlTWAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA205&lpg=PA205&dq=Surveillance+and+investigation+of+contamination+incidents+and+waterborne+outbreaks,+Hunter,+PR,&source=bl&ots=OfFUzIaBvl&sig=ACfU3U2PC0GpWDXPmOtlkaTslOmKiuxp-w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj9q5

-

Mayon-White, R. ., & Frankenberg, R. . (1989). Boil the water. The Lancet, 334, 216. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90397-8

-

Stenström, T. ., Boisen, F. ., Georgsen, F. ., & . (1994). Waterborne outbreaks in Northern Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark: TemNord, Nordisk Minist.

-

Furtado, C. ., Adak, G. ., Stuart, J. ., Wall, P. ., Evans, H. ., & Casemore, D. . (1998). Outbreaks of waterborne infectious intestinal disease in England and Wales, 1992–5. Epidemiology & Infection, 121, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0950268898001083

-

Arvanitidou, M. ., Stathopoulos, G. ., Constantinidis, T. ., & . (2001). The occurence of Salmonella, Campylobacter and Yersinia spp. in river and lake waters. Microbiological Research, 150, 38-46. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0944501311800509?via%3Dihub

-

Obiri‐Danso, K. ., & Jones, K. . (1999). Distribution and seasonality of microbial indicators and thermophilic campylobacters in two freshwater bathing sites on the River Lune in northwest England. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 87(6).

-

Savill, M. ., Hudson, J. ., Ball, A. ., Klena, J. ., Scholes, P. ., Whyte, R. ., … Jankovic, D. . (2001). Enumeration of Campylobacter in New Zealand recreational and drinking waters. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 91, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01337.x

-

Alary, M. ., & Nadeau, D. . (1989). An outbreak of Campylobacter enteritis associated with a community water supply. Canadian Journal of Public Health= Revue Canadienne De Sante Publique, 81, 268–271. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/2207948/

-

Vogt, R. ., Sours, H. ., Barrett, T. ., Feldman, R. ., Dickinson, R. ., & Witherell, L. . (1982). Campylobacter enteritis associated with contaminated water. Annals of Internal Medicine, 96, 292–296. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-96-3-292

-

Organization, W. H. (2009). Risk Assessment of Cryptosporidium in Drinking Water.

-

Fayer, R. . (2004). Cryptosporidium: a water-borne zoonotic parasite. Veterinary Parasitology, 126, 37–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.09.004

-

(1994). Assessment of inadequately filtered public drinking water. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, Vol. 43, No 36, pp. 661-669.

-

Haas, C. N., Rose, J. B., & Gerba, C. P. (2014). Quantitative Microbial Risk Assessment, Second Edition. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118910030

-

Teunis, P. ., Medema, G. ., Kruidenier, L. ., & Havelaar, A. . (1997). Assessment of the risk of infection by Cryptosporidium or Giardia in drinking water from a surface water source. Water Research, 31, 1333–1346. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0043135496003879

-

Karagiannis, I. ., Schimmer, B. ., & Husman, A. de R. (2009). Compliance with boil water advice following a water contamination incident in the Netherlands in 2007. Eurosurveillance, 14, 19156. Retrieved from https://www.eurosurveillance.org/content/10.2807/ese.14.12.19156-en

-

O’Donnell, M. ., Platt, C. ., & Aston, R. . (2000). Effect of a boil water notice on behaviour in the management of a water contamination incident. Communicable Disease and Public Health, 3, 56–59. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10743321/

-

Nauta, M. ., EG, E. ., WF, J.-R. ., Van Pelt, W. ., & Havelaar, A. H. (2005). Risk assessment of Campylobacter in the Netherlands via broiler meat and other routes.

-

Willocks, L. ., Sufi, F. ., Wall, R. ., Seng, C. ., & Swan, A. . (2000). Compliance with advice to boil drinking water during an outbreak of cryptosporidiosis. Outbreak Investigation Team. Communicable Disease and Public Health, 3, 137–138. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10902259/