General Overview

Rotaviruses are highly remarkably infectious causing diarrhea. Rotaviruses are non-enveloped viruses 70 nm in diameter that resist inactivation in the environment. They are classified into groups A through F; with group A being the most common group in humans, and is divided into four major serotypes, according to Heymann.

Although improved sanitation and hygiene greatly inhibit transmission of many other diarrheal pathogens, rotaviruses generally infected all children before 4 years of age in both developing and developed countries before rotavirus vaccine was available, according to Cook 1990 . Heymann states that Rotaviruses cause gastroenteritis with watery diarrhea, vomiting, and fever. The disease is self-limiting, lasting 3-7 days, but infection is often asymptomatic (CDC 2011) . However, rotavirus disease can be severe and lethal, particularly in underdeveloped settings; approximately 400,000 deaths per year worldwide are attributable to rotaviruses (Parashar 2003) .

Two live-virus vaccines have been developed, RotaTeq and Rotarix. They are highly effective: 74% against diarrhea and 100% against severe diarrhea for RotaTeq, and 95% against severe diarrhea for Rotarix (Greenberg 2009) .It is unclear whether these vaccines will be as effective in severely underdeveloped environments, although trials are underway (Greenberg 2009) .

Summary of data

Ward et al. fed the CJN rotavirus strain to healthy 18-45 year old men with 0.2g of NaHCO3, and measured the outcomes of infection (i.e., increased antibody titer to the CJN strain), symptoms, and detectable shedding of rotavirus. Both the virus strain and the people challenged were chosen to minimize preexisting immunity to the virus. The ID50 was approximately 6 focus-forming units (FFU); however, there were 1.56 x 104 particles per FFU. A beta-Poisson dose response model has been previously fit to the response of infection (Haas, Rose, and Gerba 1999) , yielding similar results to those presented here. Other responses (illness or shedding) indicated lower potency.

Vaccine trials have been published in which live rotavirus vaccine strains were fed to healthy human infants (Pichichero et al. 1990 , Vesikari et al. 1985) . However, their ID50 estimates were several orders of magnitude higher than that observed by Ward et al. (1986) , probably because the virus strains were attenuated. In addition, seroconversion occurred in 7/24 of the placebo recipients in one of the studies (Pichichero et al. 1990) . Therefore, these results do not appear applicable to natural rotavirus infection, and dose response models are not included here.

Piglets aged 4-5 days that had not consumed colostrum were administered porcine rotavirus (OSU strain) intragastrically (Payment & Morin 1990) . This study also showed high potency of rotavirus, with an ID50 of 40 viral particles. Tissue culture methods for quantifying this porcine rotavirus were several orders of magnitude less sensitive at detecting viable virus than visualization using electron microscopy (Payment & Morin 1990) .

When conducting risk assessments of rotavirus, the units of the dose should be carefully considered, since culture methods may inefficiently detect infectious particles (Payment & Morin 1990) or large numbers of viral particles visible with electron microscopy may be noninfectious (Ward et al. 1984, Ward et al. 1986) .

| ID | Exposure Route | # of Doses | Agent Strain | Dose Units | Host type | Μodel | LD50/ID50 | Optimized parameters | Response type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 125 | oral | 8.00 | CJN strain (unpassaged | FFU | human | beta-Poisson | 96.1 | a = 9.6E-2 N50 = 96.1 | detectable shedding |

Ward, R. L., Bernstein, D. I., Young, E. C., Sherwood, J. R., Knowlton, D. R., & Schiff, G. M. (1986). Human Rotavirus Studies in Volunteers: Determination of Infectious Dose and Serological Response to Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 154, 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/154.5.871 |

| 68 | intragastric | 10.00 | OSU (ATCC VR892) | particles | pig | exponential | 4E+01 | k = 1.73E-02 | infection |

Payment, P. ., & Morin, E. . (1990). Minimal infective dose of the OSU strain of porcine rotavirus. Archives of Virology, 112, 3-4. |

| 70 | oral | 8.00 | FFU | human | beta-Poisson | 6.17E+00 | a = 2.53E-02 k = 6.17E+00 |

Ward, R. L., Bernstein, D. I., Young, E. C., Sherwood, J. R., Knowlton, D. R., & Schiff, G. M. (1986). Human Rotavirus Studies in Volunteers: Determination of Infectious Dose and Serological Response to Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 154, 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/154.5.871 |

||

| 71 | oral | 8.00 | CJN strain (unpassaged) | FFU | human | beta-Poisson | 1.47E+03 | a = 7.28E-02 N50 = 1.47E+03 | infection |

Ward, R. L., Bernstein, D. I., Young, E. C., Sherwood, J. R., Knowlton, D. R., & Schiff, G. M. (1986). Human Rotavirus Studies in Volunteers: Determination of Infectious Dose and Serological Response to Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 154, 5. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/154.5.871 |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

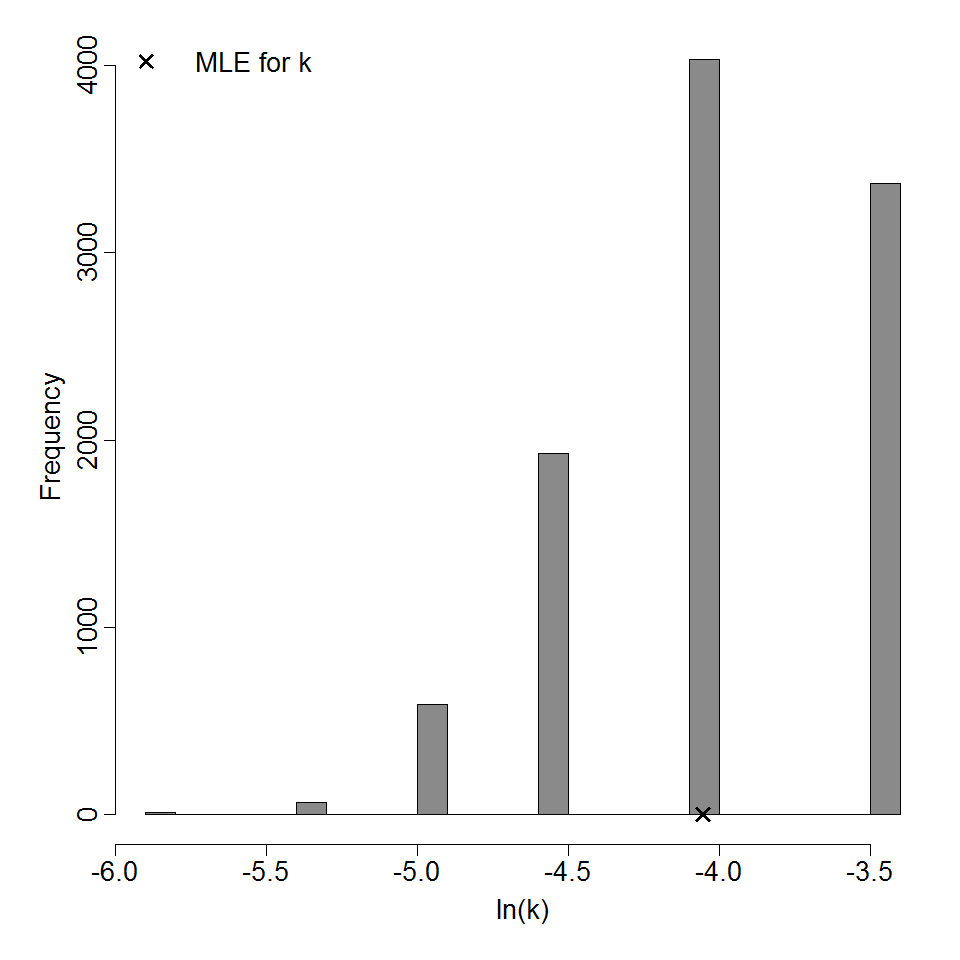

Parameter histogram for exponential model (uncertainty of the parameter)

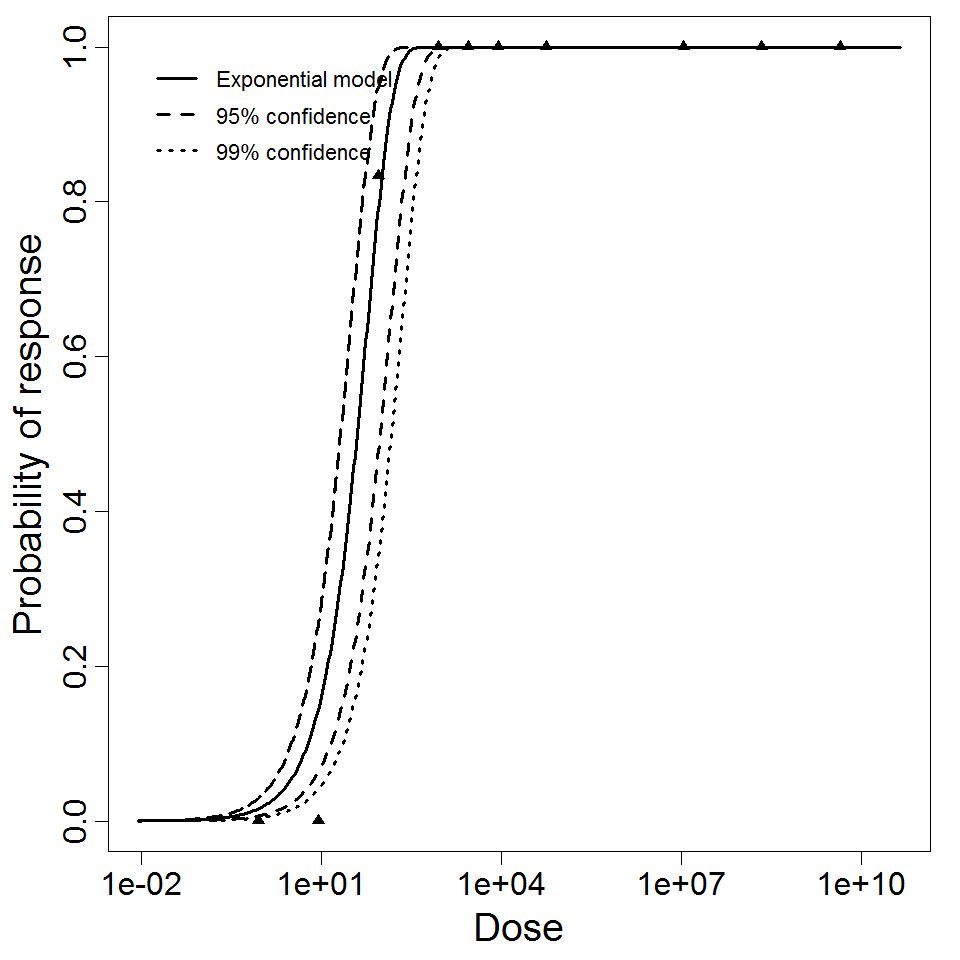

Exponential model plot, with confidence bounds around optimized model

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

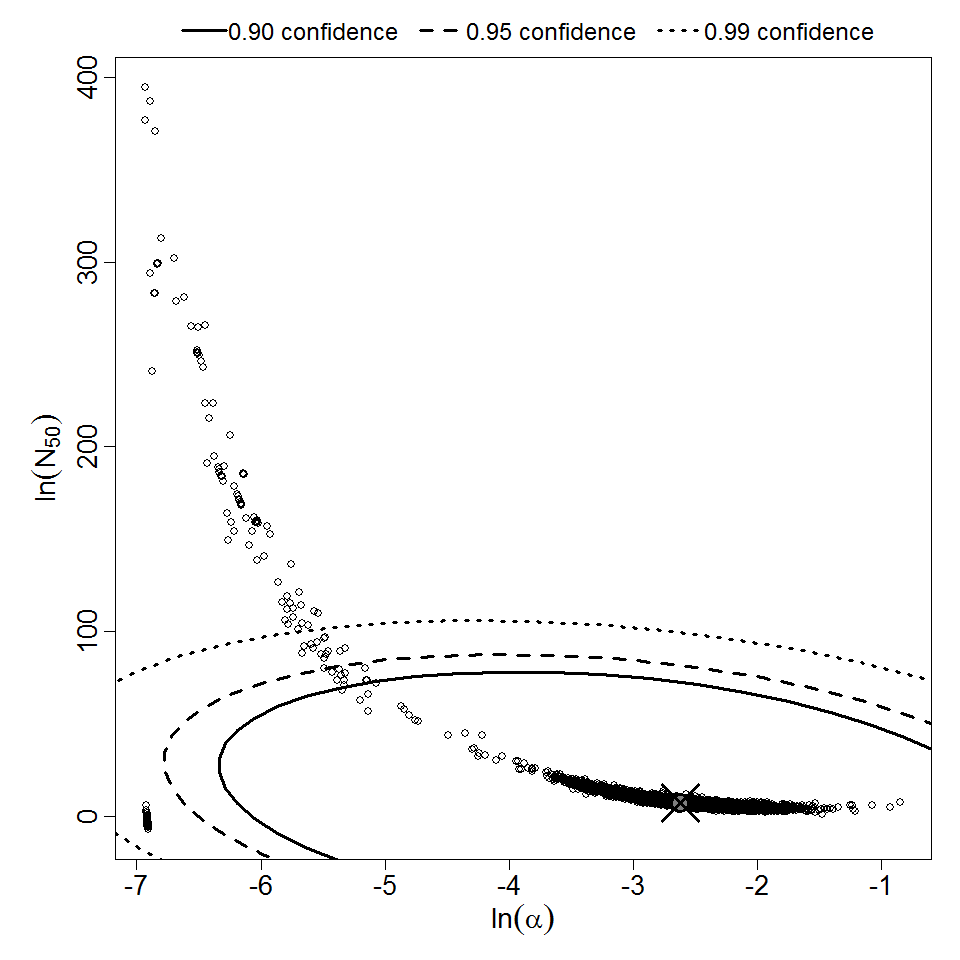

Parameter scatter plot for beta Poisson model ellipses signify the 0.9, 0.95 and 0.99 confidence of the parameters.

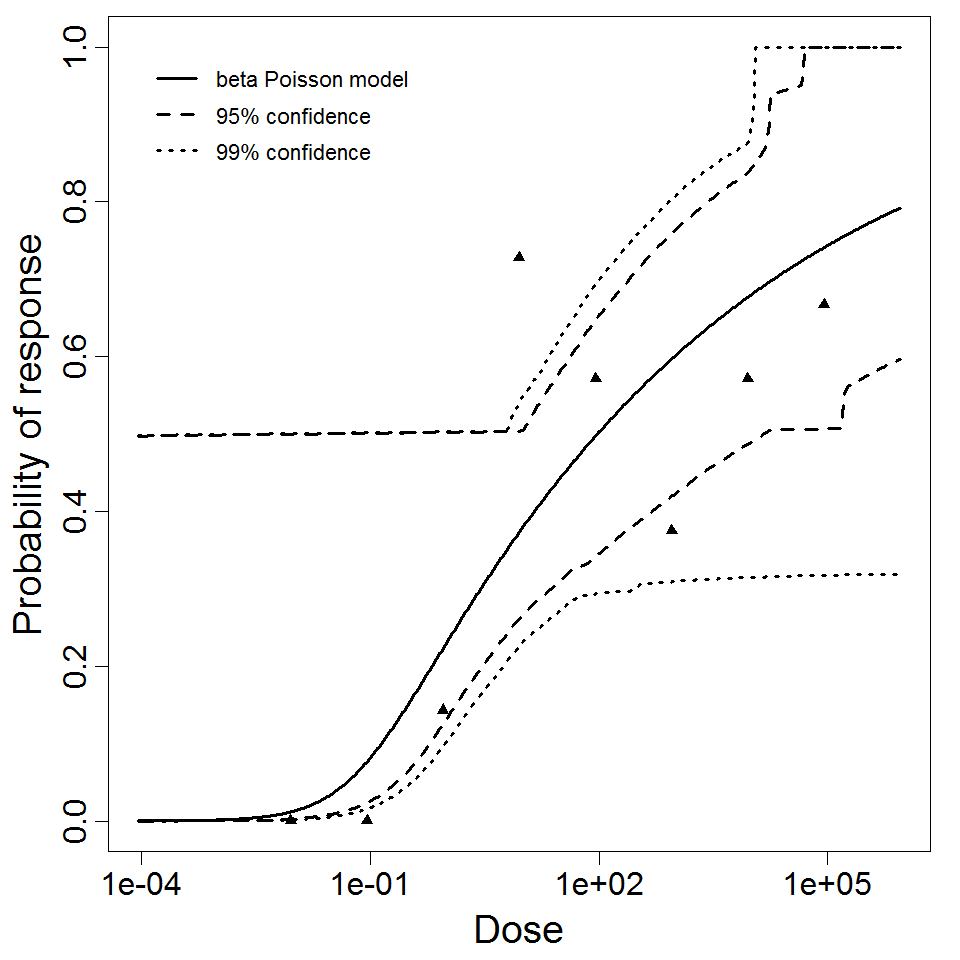

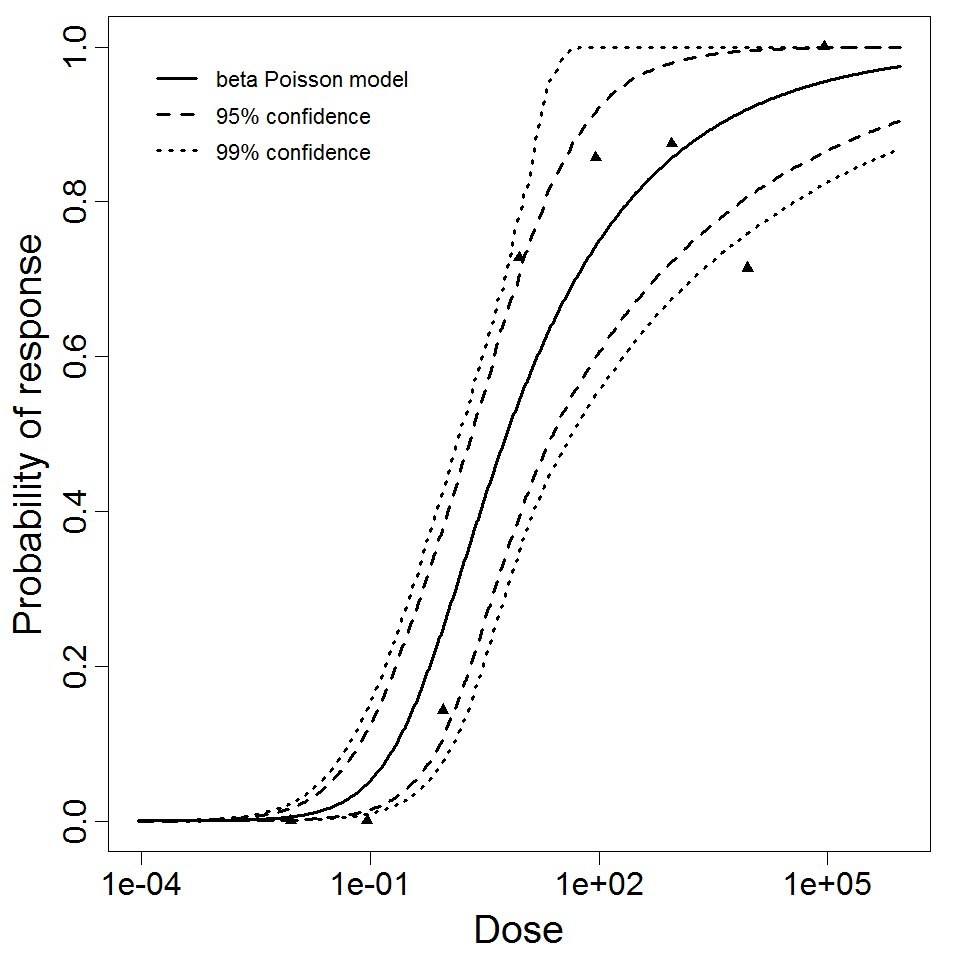

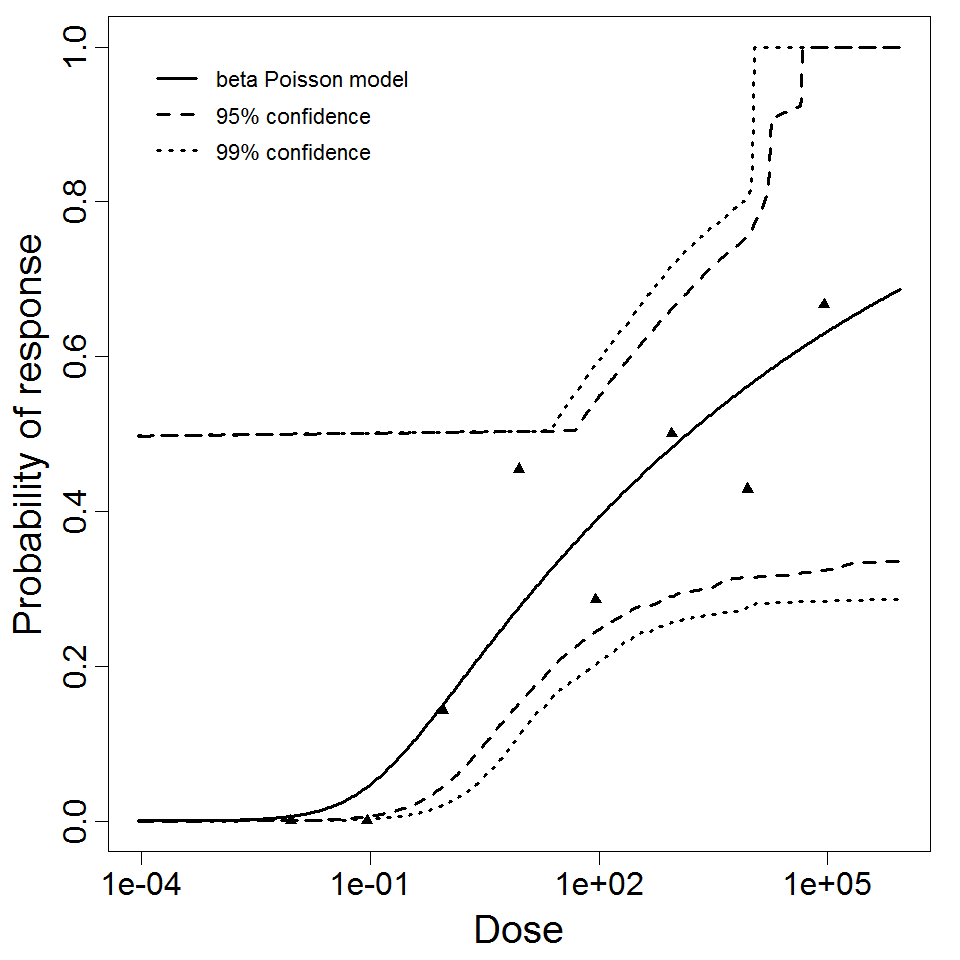

beta Poisson model plot, with confidence bounds around optimized model